Get to Know Remote Device Control Systems: A Guide to Modern Convenience

Introduction and Outline: Why Monitoring and Control Matter

To make sense of today’s connected operations, it helps to see the map before the journey. Here’s a concise outline of what this article covers and how the pieces connect:

– Section 1: A primer on why remote monitoring and control matter, plus this outline.

– Section 2: Remote Equipment Monitoring—signals, telemetry, analytics, and examples.

– Section 3: Industrial Automation System—control layers, standards, and safety.

– Section 4: Remote Device Control Systems—commands, safeguards, and cybersecurity.

– Section 5: Implementation and ROI—planning, costs, metrics, and scaling.

Monitoring and control are the heartbeat and nervous system of modern operations. When equipment health is measured in real time and commands can be executed securely from afar, organizations gain agility: maintenance becomes proactive, operators respond faster, and production aligns more closely with demand. Industry surveys frequently note that unplanned downtime carries a hefty price tag—often thousands of dollars per hour in midsize facilities—while condition-based maintenance can trim overall maintenance spend and reduce failures. These gains are not magic; they flow from better visibility, structured workflows, and careful engineering.

Three forces make this topic especially relevant now. First, the proliferation of low-cost sensors and reliable connectivity means even legacy assets can be instrumented. Second, software has matured: from time-series databases to rules engines and intuitive dashboards, insights are no longer trapped in specialist tools. Third, cybersecurity practice has advanced, making remote access defensible when designed with layered controls. The result is a practical path to smarter operations. Still, not every solution fits every plant. Environmental conditions, regulatory requirements, and latency constraints vary. This guide avoids hype, focuses on fundamentals, and will help you evaluate trade-offs with clarity.

Remote Equipment Monitoring: From Raw Signals to Actionable Insight

Remote equipment monitoring turns raw telemetry into decisions. At the edge, sensors measure vibration, temperature, pressure, flow, voltage, or environmental conditions. Those signals travel through I/O modules or edge gateways, then onward using industrial protocols such as Modbus, OPC UA, or MQTT. Data is timestamped, buffered for resilience, and forwarded to historians or cloud endpoints for aggregation. The architecture matters: buffering prevents data loss during outages, compression reduces bandwidth, and time synchronization ensures accurate comparisons across sites. A stable monitoring stack typically includes an edge agent, a secure transport, a time-series store, an alerting engine, and a visualization layer.

Value appears when monitoring changes behavior. Maintenance teams shift from periodic rounds to condition-based tasks. For example, trending vibration velocity can reveal bearing degradation weeks before a failure, allowing planned replacement during a scheduled stop. Temperature deltas between paired bearings can signal misalignment; power factor drift hints at developing electrical faults; subtle flow instability can precede cavitation in pumps. Organizations often track a core set of indicators to tie monitoring to outcomes:

– Downtime-related: mean time between failures (MTBF), mean time to repair (MTTR).

– Performance: energy per unit produced, cycle time variance, throughput stability.

– Quality: scrap rate, first-pass yield, process capability indices over time.

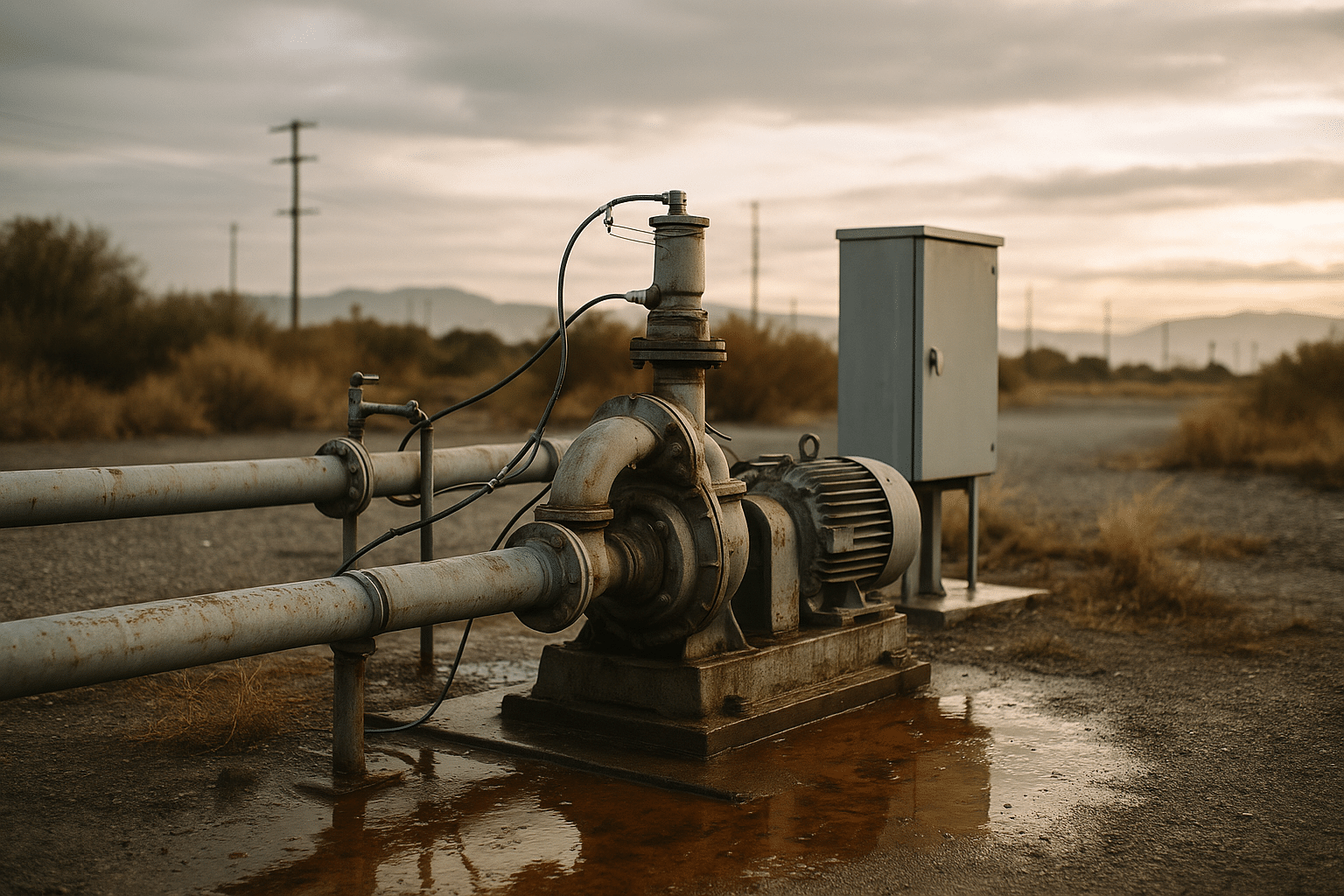

Consider a remote water transfer site. With level, flow, and vibration sensors, the team detects rising vibration on a critical pump while flow remains within targets. An alert, routed to an on-call engineer, triggers a video inspection and a planned swap to a standby unit. The original pump is serviced off-line, and the site avoids a high-cost emergency dispatch. Across a fleet, similar interventions compound. Industry assessments regularly cite double-digit reductions in unplanned downtime when condition indicators are systematically tracked and acted upon. The caveat: data must be trustworthy. Calibration routines, sensor placement, and error detection (for example, plausibility checks and redundancy on critical measures) are as important as the analytics themselves. Without disciplined data quality, even the sharpest dashboard becomes a mirage.

Industrial Automation System: Control Layers, Standards, and Reliability

An industrial automation system coordinates sensors, actuators, and logic to achieve consistent outcomes under variable conditions. Think of it as a layered stack. At the field level, transducers and drives interface with the physical process. A controller layer—often programmable logic controllers (PLCs) or similar devices—executes deterministic logic for interlocks, sequencing, and closed-loop control. Supervisory systems provide visualization, alarming, and data collection. Above that, manufacturing execution and planning layers align production with orders, quality procedures, and materials. Each layer has a clear purpose: fast, deterministic cycles stay near the process; slower, analytical decisions move up the stack.

Standards create a common language and raise the reliability bar. Programming models defined for industrial controllers encourage consistent, reviewable logic. Integration frameworks help partition responsibilities between operations technology and information technology. Cybersecurity guidance specific to industrial environments supports segmentation, patch management, and incident response. For the network, robust topologies—such as ring configurations with rapid recovery—improve availability, while segmentation and allow-listing confine traffic to known pathways. Safety practices matter, too. Safety integrity levels offer a method to match risk reduction to hazard severity and probability, and safety relays or dedicated safety controllers provide hardware-enforced stops independent of general control logic.

Performance measures anchor decisions. Overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) ties availability, performance, and quality into a single lens; moving from a low baseline to a higher one often yields substantial output without new capital equipment. In a food packaging line, for instance, automating changeovers with recipe management and verifiable setpoints cuts errors and shortens restart time. Energy management integrated into control logic can schedule high-load operations when tariffs are favorable. Meanwhile, historian data feeds continuous improvement: root-cause analysis of nuisance alarms, cycle time histograms, and alarm shelving reviews often reveal configuration issues or training gaps. The big picture is steady: automation is not a silver bullet, but combined with disciplined operations and a feedback culture, it becomes a durable engine for quality and throughput.

Remote Device Control Systems: Commands, Safeguards, and Cybersecurity

Remote control is the power to change setpoints, start or stop equipment, and reconfigure systems without being physically on site. That power must be bounded by engineering discipline. A robust design layers interlocks, confirmations, and fallbacks so that a single mistake cannot propagate into a process upset. Command arbitration ensures that local emergency stops override remote commands; operating modes (local, remote, maintenance) prevent accidental actuation during service; watchdogs and heartbeats detect stale connections and force safe states. The control plane should be distinct from the monitoring plane, with minimal, well-defined write paths that are auditable and rate-limited.

Network realities shape control behavior. Latency and jitter influence which actions can be performed remotely; slow, drift-tolerant setpoint changes are usually safe, while sub-millisecond motion control belongs on site. Queued commands, idempotency, and sequence numbers avoid duplication or out-of-order execution. Time-bounded operations (for example, “start pump for 20 seconds unless acknowledgment received”) reduce risk if communications fail. Clear human-machine interface patterns—confirmation dialogs for critical writes, color conventions, and alarm priorities—lower cognitive load. Where multiple controllers exist, a tie-breaking and ownership model prevents conflicts.

Security is non-negotiable. A defensible remote control setup uses layered safeguards:

– Strong identity: unique credentials per user and device, multifactor authentication, and role-based access control.

– Hardened transport: encrypted channels, certificate-based trust, and segmentation that isolates control networks.

– Integrity and provenance: signed firmware, secure boot, and tamper-evident logs.

– Observability: comprehensive audit trails for every write, plus anomaly detection for unusual command patterns.

Equally important is usability under pressure. During an incident, operators need simple, reliable actions: switch to local mode, invoke predefined safe states, and view a concise timeline of recent commands and alarms. Training simulations that replay real data help teams practice responses without risk. Post-incident reviews should analyze not only technical faults but also human factors—ambiguity in labels, poorly grouped alarms, or missing confirmations. When remote control marries safety, clarity, and security, it becomes an asset that extends human capability rather than a point of fragility.

Implementation, Costs, and ROI: A Practical Roadmap

Getting from idea to dependable operations follows a structured path. Begin with discovery: catalog assets, critical failure modes, existing networks, and compliance constraints. Draft use cases tied to measurable outcomes—reduce unplanned downtime on a compressor bank, trim energy per unit, or shorten changeovers. Perform a risk assessment to understand safety and cybersecurity implications, then choose a pilot scope small enough to manage yet representative of real complexity. Pilot with explicit success criteria and a rollback plan. Treat documentation as a deliverable: network diagrams, asset inventory, data flows, and a clear RACI for incident response.

Costs span more than devices and software. Total cost of ownership typically includes:

– CapEx: sensors, gateways, controllers, networking, and installation.

– OpEx: connectivity, software licensing, support, and maintenance.

– People: training, procedures, and time for cross-functional collaboration.

– Security: certificate management, patching processes, and monitoring tools.

ROI emerges from avoided downtime, lower maintenance spend, better energy use, and improved yield. A simple model ties benefits to KPIs. Suppose a line experiences eight hours of unplanned downtime per quarter, with an estimated impact of five thousand per hour. If monitoring and interlocks reduce that by 30%, the annual avoidance is meaningful before counting energy and scrap reductions. Add softer benefits—safer interventions due to remote diagnostics, faster onboarding thanks to standardized dashboards—and the case strengthens. Keep the math honest by including the run costs of data storage, connectivity, and lifecycle updates.

Scale carefully. After the pilot, standardize device profiles, naming conventions, and alert policies. Introduce change control so firmware updates and logic changes follow test-and-approve steps. Segment networks early; retrofitting segmentation later is disruptive. Plan for resilience: spares strategy, documented failover, and routine drills. Finally, look ahead without overcommitting. Edge analytics can filter noise and spot anomalies closer to the process; private wireless networks can extend coverage in challenging sites; digital twins can accelerate commissioning and scenario testing. The steady approach—start focused, measure ruthlessly, scale what works—tends to produce durable wins and a team that trusts the system they operate.